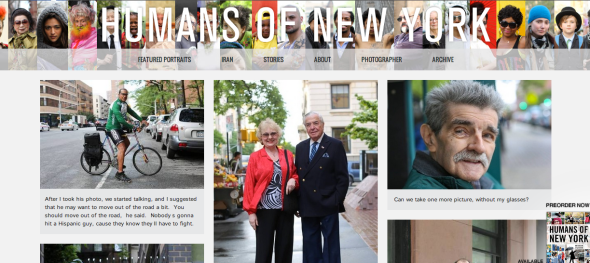

Like most humans of the internet we are fans of Humans of New York (HONY).

HONY reminds us that everyone has a story as they glide in and out of our own lives as extras, maybe appearing as “couple in coffee shop” or “crying kid on airplane.” HONY gives us a glimpse of those lives and hints at the greater depth of the “man in the corner.”

That’s why a recent story in the New Yorker critiquing Humans of New York, along with other storytelling projects such as TED and the Moth, caught our eye.

A few of the critiques in “Humans of New York and the Cavalier Consumption of Others” by Vinson Cunningham and how we view the critiques:

The not deep enough critique:

Once an arrangement of events, real or invented, organized with the intent of placing a dagger—artistic, intellectual, moral—between the ribs of a listener or reader, a story has lately become a glossier, less thrilling thing: a burst of pathos, a revelation without a veil to pull away. “Storytelling,” in this parlance, is best employed in the service of illuminating business principles, or selling tickets to non-profit galas, or winning contests.

“Stories” [the HONY book] betrays shallow notions of truth (achievable by dialogic cut-and-paste) and egalitarianism.

My thoughts: So books are deep enough? Lengthy pieces in the New Yorker accompanied with hand-drawn portraitures are deep enough? HONY is simply a different type of storytelling. One isn’t necessarily better than the other. HONY reaches people where they are and likely reaches way more people than the commitment of reading in-depth reportage. HONY may introduce us to a lifestyle we don’t know and act as an entrance to exploring more to find the broader context and depth.

The it’s not a standalone photo critique:

The quick and cavalier consumption of others has something to do with Facebook, Humans of New York’s native and most comfortable medium. The humans in Stanton’s photos—just like the most photogenic and happy-seeming and apparently knowable humans in your timeline—are well and softly lit, almost laminated; the city recedes behind them in a still-recognizable blur. We understand each entry as something snatched from right here, from someplace culturally adjacent, if not identical, to the watcher’s world; there’s a sense (and, given Stanton’s apparent tirelessness, a corresponding reality) that this could just as easily be you, today, beaming out from the open windowpane of someone else’s news feed. Any ambiguity or intrigue to be found in a HONY photo is chased out into the open, and, ultimately, annihilated by Stanton’s captions, and by the satisfaction that he seems to want his followers to feel.

One of the great joys, after all, of looking at a portrait is the imperfectible act of reading a face. Is that a smile or a leer? Anguish or insight? Focus or fear? “Stories” offers answers before the questions have a chance to settle.

My thoughts: So we should never pair stories with photos? If this really is a problem for Mr. Cunningham, just don’t read the captions.

The consuming people critique

This really isn’t cited in the story, and maybe it’s something I ‘m just overly sensitive toward, but the title itself leads the reader to believe that HONY is exploiting people and benefiting from it.

My thoughts: I’ve been criticized on occasion for exploiting the people I write about. It’s something I’m always conscious of because I do meet people, listen to their stories, write their stories, and ultimately get PAID to share those stories. BUT if I did not get paid to tell the stories, I would be working some other job and those stories wouldn’t get told. Stories aren’t commodities, they are people’s lives, and if I’ve started to see people’s lives as things to be bought and sold, I hope that I would hang up my Moleskine and find something else to do. Stories are meant to educate the reader and to be felt by the reader. That’s my purpose, that’s the purpose of what we do at the Facing Project, and I believe that’s the purpose of the work done by HONY.

—

There’s no one way to tell a story. I enjoy the New Yorker. But while I find value in it’s in-depth works of journalism and opinion, we live in a time that doesn’t value long form journalism as it once did. [If you want to get more long form journalism subscribe to longform.org which highlights past and present long form works from a diverse group of sources.] But much of this New Yorker piece is a critique of society’s shorter attention span and those storytellers who have succeeded at it.

Some of these criticisms are pretty weak, and are along the lines of, “I want this thing to be a different type of thing.” Mr. Cunningham writes this for instance: “…the truest thing about a person, that person’s real story, is just as often the thing withheld—the silent thing—as the thing offered.”

I mean, I wish I could read minds. I wish that I had Wonder Woman’s lasso of truth, but, like most of this critique, that’s not reality.