In 2005, I traveled to Honduras because my T-shirt was made there. Silly reason, I know. And it felt silly once I showed up at the factory where it was made to meet the workers.

I met Amilcar who was 25. We chatted for a few minutes and then we went our separate ways. I became obsessed with where clothes came from and what life was like for the people who made them, and eventually wrote a book about the obsession: Where Am I Wearing? A Global Tour to the Countries, Factories, and People That Make Our Clothes. Unbeknownst to me Amilcar became obsessed with going to the United States to improve the life of his three daughters.

I traveled back to Honduras in 2011 to find Amilcar and learned he was gone. He was in California. Eventually, I visited Amilcar in California and he told me about his journey.

In many ways, Amilcar inspired me to become a storyteller. No matter where you stand on the issue of immigration in the United States, you can’t argue with Amilcar’s story, the risk he took for his family, and the life that he provides them with today. He showed me how powerful a story can be.

The passage below is excerpted from Where Am I Wearing? and is about the moment Amilcar first stepped into the United States after months of riding on top of trains in Mexico and dodging police and thugs.

We originally share this story as part of our Facing Immigration national project. It was our first attempt at a national project. Despite our efforts to reach out to community partners for the project, we were unable to secure one. In light of recent news, it seems they may have been overwhelmed.

The journey that Amilcar made is not an uncommon one, and one often undertaken by children. About 52,000 children traveling without parents have been caught at the Southwest Border since October.

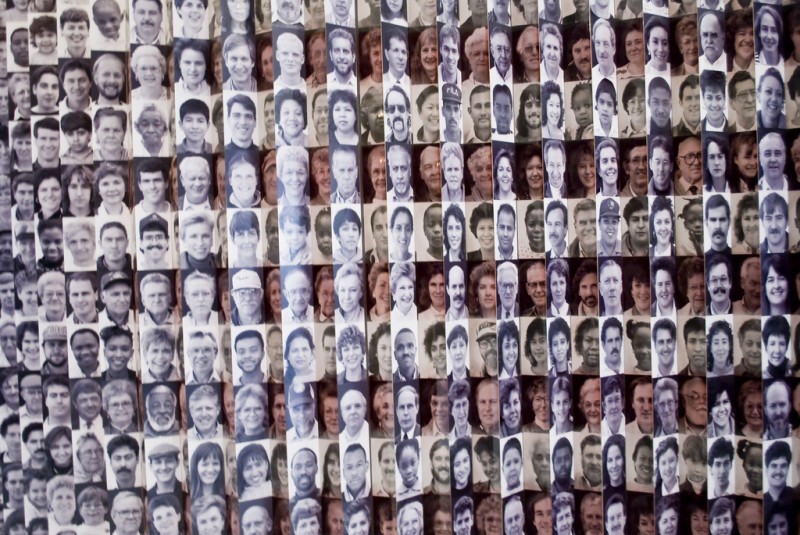

We chose Amilcar’s story, although not a typical Facing Project story, as our story of the week because each of these 52,000 children has a story.

///

They run for the fence.

Amilcar’s fingers lace through the chain links and pull – his knuckles white, his fingertips the first part of him to complete the journey of more than 2,000 miles. He hikes one leg over, then the other, and drops into the United States.

He made it.

The bandits close fast and are climbing the fence after Edwin. Amilcar has known Edwin since before he could remember. He was the one who knew the way to the United States. Tired and weary they had hung onto the sides of speeding trains. They had hiked through the desert until their shoes were worn through. They had dodged rocks thrown at them from the residents of Chihuahua. They had experienced unspeakable hardships and unexpected kindnesses. And now the bandits were at Edwin’s ankles, trying to pull him back into Mexico and do God knows what to him.

Amilcar grabs a rock. He scrapes it back and forth across the chain link fence. The sound is a metallic zip interrupted only by the howls of the bandits as the rock rakes across their fingers.

Sorry about your fingers, Amilcar thinks, but he’s my cousin.

Edwin makes it.

They enter the United States just as they had entered Mexico – bloody, afraid, and broke.

The border patrol officers greet them: “Where did you come from?”

“Mexico,” the cousins say.

“Prove it. How many colors are on the Mexican flag?”

The cousins answer correctly.

“Who is the president of Mexico?”

Again the cousins answered correctly just as they do all of his questions. They had spent the past two months in Mexico, how could they not know such simple questions!

After narrowly escaping the machete carrying bandits, Amilcar and Edwin are detained at 6 PM. By 3 AM they are back in Mexico with a voucher courtesy of the U.S. government for a bus ticket to Michoacán, Mexico, where they said they were from. Tickets at the bus station are two for the price of one. They get two tickets to Mexicali where they hope to cross into Arizona.

An old man in Mexicali named Artemio takes them in. They stay with him for twenty-five days, during which they call relatives to line up the $2,000 to pay a coyote to take them to Indio, California. Amilcar couldn’t reach his friend in New York and decides to head to Indio where his uncle lives.

Under cover of darkness, they crawl across the border into the desert through a canal. They crawl for four hours and then they wait in a grass field.

From October 2006 to May 2007, 31,993 migrants were apprehended by the U.S. Border patrol and six migrants were found dead. Migrants drown in ditches. They die of exposure to the heat and the cold. They die of thirst. They are murdered by vigilante militiamen.

In April, President Bush gave a speech in nearby Yuma, praising the lockdown on the American border. No one is certain how many have crossed, but the number of apprehensions are down 68% in Yuma. The previous six months only 25,217 immigrants had been apprehended compared to 79,131 the same period the year before.

“When you’re apprehending fewer people, it means fewer are trying to come across,” President Bush said. “And fewer are trying to come across because we’re deterring people from attempting illegal border crossings in the first place.”

U.S. officials estimate that 12 million immigrants live in the United States and despite 13,000 border patrol agents patrolling the border, 400,000 more come each year. Amilcar was now among them.

Three months ago he had hugged Betsabe goodbye. He had been mugged, hugged, and deported.

A truck takes them to a hotel room with thirteen other tired and dirty, nervous and ecstatic migrants. Two box trucks come to the hotel and Edwin is told to get into one and Amilcar the other.

Now, Amilcar is alone; his fate in the hands of smugglers.

The coyote directs fourteen other migrants into cram in the back of the truck with Amilcar and shuts the door. Eight hours later, the door is thrown open and for the first time, Amilcar blinks the United States into focus.

///

That’s part of Amilcar’s story Facing Immigration. What’s yours? Join the project and share.